Sayger: The First Superstar

Herman Sayger, Culver High School, 1911-1914

By Ken Johnson

His place should be secure on any Marshall County all-time basketball team. Instead, his accomplishments are almost unknown, his name forgotten with the passing of the Culver High School athletic award which carried his name.

Herman Earl "Suz" Sayger, arguably among the finest athletes ever to come out of Marshall County, deserves a better fate.

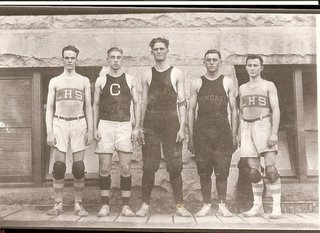

TOP PHOTO: The 1914 Indiana

All-State Team (Sayger is second

from left).

RIGHT PHOTO: Sayger in

Heidelberg College football

uniform (circa 1917).

Consider this: Sayger made several Indiana high school all-state basketball teams as a Culver High School senior in 1914, earned letters in five sports at Heidelberg College in Ohio (even coaching the football team while the regular coach was serving in World War I), played professional football, helped broadcast college football games with Red Barber, and founded a sports syndicate in which he wrote and published 24 books on athletics in conjunction with famous coaches.

But it was in basketball where he left his mark. He didn't start the first game, against Bremen, in his freshman year, but came in to play in the second half and scored four points. He was a starter the rest of his career, leading his team to 44 wins, 10 losses and one tie.

The Culver teams of those days played in what we would call very primitive facilities. Few gyms were used, and most teams rented a large room or hall. But outside courts were also used, as well as hay lofts and church basements.

In 1913 and 1914, Culver played upstairs in a building called Captain Crooks Hall on the north side of Lake Maxinkuckee. The seating capacity was about 50, with the dressing room in a downstairs pantry equipped with two buckets, according to descriptions supplied by the late Bob Rust, the late Paul Snyder Sr. and the late Rex Mawhorter.

The lights were gas burners and every time they were bumped, a timeout had to be called to relight them. At times on cold nights, the floor was covered with a film of ice because stoves didn't produce enough heat. The ceiling was only 14 or 15 feet high, so long, arched shots were out of the question. The wire and walls were the out-of-bounds lines.

"It was hell to play in," remembers Mawhorter.

The hall had to be rented for games and the team was also able to rent the hall two nights a week for practice. The rest of the time, weather permitting, practice was held outdoors.

In the summer, they played in the ice houses. Just getting to out-of-town games presented some problems. Trains were used for most games, which explains why teams like Plymouth played Columbia City, Warsaw, Wanatah and Valparaiso. No transfers had to be made on that line.

When Culver played Winamac, the team had to go by way of Logansport. (The Wakarusa basketball team reportedly once made the trip to play Bremen by horse and sleigh.)

And it was up to the home team to pay all expenses for the visiting team. For example, Culver in 1914 left early Friday, March 6, and traveled to Kokomo. The team members ate when they arrived, and then played Kokomo that night. They stayed with families in Kokomo that night, and then on Saturday morning, they boarded the train and got off at nearby Galveston to play a Saturday afternoon game on the way home.

During his sophomore year, in 1911-12, Sayger led the Culver team to the 13th Congressional District title, which is how the tournament was organized in those days. The championship game, played at Rochester, against South Bend High School, ended in a 2-0 forfeit when the South Bend coach pulled his team from the floor after his star player was called for his second "class B" foul for tripping a Culver player. (The rules in those days classified fouls as A and B, with the player being ejected from the game if he picked up two class B fouls.)

At the University of Notre Dame three days later, with more than 100 Culver fans on hand via a special train, the dream of a trip to the state finals was ended by Whiting, 15-12. Sayger scored 10 of his team's points.

During his junior year, Culver won 11, lost two and tied one. The season was highlighted by a great three-game series with Rochester, a perennial power in those days. The first game, played on Nov. 27, 1912, ended in a 26-26 tie amid controversy; the Culver scorekeeper had Culver ahead 27-26, but the game was declared a "no-decision" by the Indiana High School Athletic Association.

Culver won the second game, 31-23, played at home on Jan. 29, 1913, with Sayger making 29 of the 31 points. The final game was played at Rochester on Feb. 12, 1913, with the hosts winning 35-27. Sayger tallied 19 points. Rochester later lost a 19-17 overtime decision in the state tourney to eventual champion Wingate. Culver also played in the state tourney at Bloomington, losing a first-round game to Lafayette 27-24. Lafayette reached the final four before losing to Wingate.

Culver was the dominant team in northern Indiana in Sayger's senior year. Playing a tough schedule against teams from LaPorte, Rochester, Elkhart and Kokomo, Culver won them all except for a one-point loss at Kokomo. Two of the wins came against Rochester, one by 20 points.

Sayger had an outstanding year, scoring 561 points (56 percent of the team's total) in 19 games for a 29.5 average. That's a remarkable total in any era, but becomes incredible considering Culver's opponents averaged only 16 points a game. He had high games of 79 points against North Bend, 55 against Plymouth and at least 52 against North Judson (the newspaper account shows 26 field goals, but not the free throws.) But much of his schoolboy career is a mystery, as newspaper accounts and box scores of many of his games are missing.

The biggest mystery is the night of March 8, 1913, in Culver's Brooks Hall when he very likely scored 113 points against a first-year, and obviously outclassed, Winamac team. It was Bob Rust of Culver, the former editor of the Culver Citizen who knew almost everything about Culver, who said that he had been told by the late Edgar("Tone" Shaw, who played for Culver in those years, that Sayger had scored more than 100 points in a game.

Mention was also made in Culver Military Academy's newspaper, the "Vedette," supplied by Sayger's widow, that Sayger had once scored 114 points (not 113) in a game. The information had been furnished to the Vedette by former teammates Rex Mawhorter, Charles Cowen and Tone Shaw.

More "evidence" was supplied in an Associated Press story on Jan. 1, 1952, which was carried in the South Bend Tribune. The article reported that Sayger was going to be honored later that week when Heidelberg dedicated the Sayger basketball court at the university's Seiberling Gymnasium, and added, without any elaboration or more detail, that Sayger had once scored 113 points, on 56 field goals and one free throw, in a high school game.

The 113-point game was also mentioned by Edwin Butcher, retired Heidelberg alumni secretary, at the memorial service for Sayger at Heidelberg on Feb. 1, 1970, a week after Sayger's death. But which game? This was well before the time when basketball grabbed hold of Indianans' hearts, and newspapers often overlooked the games played by the local high schools. Reporters rarely attended games.

There were three games in which Culver, as a team, topped the 113-point mark. Records show a 115-24 win over Plymouth, in which Sayger scored 55 points, and a 137-7 win over North Bend, in which he scored 79 points; both of those games were in his senior year and were reported in a newspaper.

But records can't be found for the 154-10 win over Winamac on March 8, 1913, during his junior year. It is that game, and that night, which may have involved a state-record performance.

Rex Mawhorter, Sayger's teammate who was tracked down in California in 1983, confirmed in a telephone call that, yes, Sayger had once scored 113 points and, yes, it had come against Winamac. Sayger's widow said her late husband sometimes mentioned to her that he had once scored 113 points in a high school game, and some of his friends would talk about it when they visited.

After High School

When the opportunity of a scholarship at Culver Military Academy arose, Sayger accepted it, playing four sports during the year he spent on Lake Maxinkuckee's shore. Although he had never played football before, Sayger made the Academy team as a left end and soon became one of its stars. He also led the basketball team in scoring, averaging 18 points a game.

After High School

When the opportunity of a scholarship at Culver Military Academy arose, Sayger accepted it, playing four sports during the year he spent on Lake Maxinkuckee's shore. Although he had never played football before, Sayger made the Academy team as a left end and soon became one of its stars. He also led the basketball team in scoring, averaging 18 points a game.

The Vedette, on Dec. 5, 1914, reported: "Among the men who starred this season is Herman Sayger. This is his first year for football, but nevertheless he showed great ability in several ways. He handles the forward pass with exceptional skill and is a good man on the defensive and offensive. He is very quick and an excellent open field runner. Taken altogether, he is a very good all-round man and has scored a big hit with the fellows. It is expected that he will play a better game of basketball as it is his specialty."

During the summer of 1915, Sayger worked at a freight office in Indianapolis, coming in contact with some Purdue men. With his trunk packed and his pipe bought (as was the advertising image of college men in those days), he was planning on heading for West Lafayette for his college career. But on Sunday, two days before he was to leave for Purdue, he decided to take one last sail on the lake, leaving at 9 a.m. with the wind at his back and returning at 3 p.m., paddling back to his starting point.

Greeting him on the dock was Coach Ike Martin of Heidelberg College, who had been waiting for him since 10 a.m. When Sayger learned that he could make most of his way at Heidelberg by working, he changed his mind and instead of leaving for Purdue on Tuesday, he traveled to Tiffin, Ohio, on Monday.

During the summer of 1915, Sayger worked at a freight office in Indianapolis, coming in contact with some Purdue men. With his trunk packed and his pipe bought (as was the advertising image of college men in those days), he was planning on heading for West Lafayette for his college career. But on Sunday, two days before he was to leave for Purdue, he decided to take one last sail on the lake, leaving at 9 a.m. with the wind at his back and returning at 3 p.m., paddling back to his starting point.

Greeting him on the dock was Coach Ike Martin of Heidelberg College, who had been waiting for him since 10 a.m. When Sayger learned that he could make most of his way at Heidelberg by working, he changed his mind and instead of leaving for Purdue on Tuesday, he traveled to Tiffin, Ohio, on Monday.

He arrived in Tiffin, he wrote, with $4.50 in his pocket and no dorm room or books. Two days later, disgusted with his lot (the first night at Heidelberg he reportedly slept on a dorm floor), he started for the train station and was ready to go home. But an assistant coach talked him out of it, offering Sayger a place in his own home for that night. And that's where Sayger stayed the rest of the school year. At Heidelberg, he was named all-Ohio in both football and basketball. His 39 points against Hiram in 1919 still stands as the sixth highest point total for a single game. When Coach Martin went into the service in 1917, leaving Heidelberg without a coach, Sayger was selected to guide the team.

Willis Gebhardt, the right end on that team, recalled there wasn't too much question about choosing the interim coach. "It seemed to be the natural thing for Sayger to take over. He was liked by everyone. He had a magnetic personality. He didn't have any enemies." Gebhardt said Sayger had no trouble whatsoever. "We lost one game 3-0 and tied Oberlin. We won all the others. We were not a bunch of fellas who were factionalized."

The school annual credited Sayger for the success of the team, saying he had "unusual qualities of leadership" and "won the confidence of the players."

Willis Gebhardt, the right end on that team, recalled there wasn't too much question about choosing the interim coach. "It seemed to be the natural thing for Sayger to take over. He was liked by everyone. He had a magnetic personality. He didn't have any enemies." Gebhardt said Sayger had no trouble whatsoever. "We lost one game 3-0 and tied Oberlin. We won all the others. We were not a bunch of fellas who were factionalized."

The school annual credited Sayger for the success of the team, saying he had "unusual qualities of leadership" and "won the confidence of the players."

"I was very close to Sayger," Gebhardt said. In fact, Gebhardt tutored him in mathematics. "I just wanted to do something nice for him. I had great respect for Herman Sayger.

"He was a terrific basketball player. He could really dribble down the floor. He could get around two players wihtout any trouble at all," Gebhardt said Sayger was about 160 pounds and 5-foot-10. "His cleverness and agility" were the keys to his ability.

Gebhardt said Sayger played football, basketball and baseball. "He was an all-round athlete." In baseball, he was usually the catcher, but sometimes he traded places with the team's star pitcher. In 1917, Coach Martin took Sayger along to play professional football at Massillon, Ohio. To protect his eligibility, Sayger's widow said, he was called "the kid." It was here that he first met Knute Rockne.

In 1918, Sayger too went ino the army, but still kept active in sports by playing basketball and football at Camp Dodge, Iowa. After graduating from Heidelberg in 1920 and coaching a few years in high schools, he was an assistant at the University of Akron for three years, coaching football, basketball and track. During that time, he also served as advisory coach to Frank Nead's professional Akron Indians and as a scout for Jim Thorpe and his Canton team.

In 1924, he was appointed coach and athletic director at Heidelberg College. He served for seven years, taking a losing athletic program and turning it into a winner. Two of his football teams went undefeated, playing against schools with much larger enrollments.

During this time, he organized the Tiffin Downtown Coaches, which may have been the first athletic booster organization in the country. After retiring from coaching because of health problems, he started Sayger Sports Syndicate.

In the fall of 1935, when Ohio Oil Co. contracted to broadcast all of Ohio State's football games, Sayger was signed as associate announcer, with Red Barber of WLW, Cincinnati, as chief. The pair worked eight games together, Barber relating the running account and Sayger contributing atmosphere, "side-lights," chats from the dressing rooms, talks from the grandstand, and so on. He carried a short-wave sending set wherever he went and was thus able to interview spectators in the boxes, players and coaches on the field and benches, and relay these interesting bit to the main wire in the radio room, and thence to the air fan via WLW.

His widow, who knew him from her grade-school days in rural Tiffin and started working for him shortly after her high school graduation in 1933, remembered those days when he illustrated books on athletics and she was the fill-in artist. Once, she said, he sent a book to be approved by a coach on his board of directors and received the reply: "Sayger, you know more than we'll ever know." He sold the books to colleges and traveled extensively. He came up with the idea of a pocket handbook of 350 to 400 schedules of college teams, taking it to a friend at Ohio Oil (now Marathon) at nearby Findlay with the idea of circulating the schedules. An advertising man was called while Sayger was still in the office and a project was born; the schedules were distributed to college alumni. Mrs. Sayger also said that he was the first to write an all-sports pictorial magazine, which was called "Sports Spotlight." He is also credited with publishing the first set of hand signals for football officials.

He took pictures on his travels, and when he sometimes had trouble getting film back on time from a nearby camera store, he bought the store in 1933. By 1940, the business included cameras and advertising specialities. He took over a printing plant and moved it downstairs. The company made photo cuts for newspapers and provided photostating. "There was no end to what he did," Mrs. Sayger said.

"I loved everything he tried," she added. "We had so much in common. He was a great person to work for. People loved him. He was so kind, and always thought of the other fellow." His time was still occupied by writing and composing music, but, as Mrs. Sayger said, "he got into lots of things. He was never idle. He took correspondence courses in everything. He was a tremendous worker"

"He loved athletics and music," said Mrs. Sayger, who was married to him only a few years before his death (he had been a widower). "He practiced by the hour when he was growing up, dividing his time between athletics and music."

Gebhardt said Sayger played football, basketball and baseball. "He was an all-round athlete." In baseball, he was usually the catcher, but sometimes he traded places with the team's star pitcher. In 1917, Coach Martin took Sayger along to play professional football at Massillon, Ohio. To protect his eligibility, Sayger's widow said, he was called "the kid." It was here that he first met Knute Rockne.

In 1918, Sayger too went ino the army, but still kept active in sports by playing basketball and football at Camp Dodge, Iowa. After graduating from Heidelberg in 1920 and coaching a few years in high schools, he was an assistant at the University of Akron for three years, coaching football, basketball and track. During that time, he also served as advisory coach to Frank Nead's professional Akron Indians and as a scout for Jim Thorpe and his Canton team.

In 1924, he was appointed coach and athletic director at Heidelberg College. He served for seven years, taking a losing athletic program and turning it into a winner. Two of his football teams went undefeated, playing against schools with much larger enrollments.

During this time, he organized the Tiffin Downtown Coaches, which may have been the first athletic booster organization in the country. After retiring from coaching because of health problems, he started Sayger Sports Syndicate.

In the fall of 1935, when Ohio Oil Co. contracted to broadcast all of Ohio State's football games, Sayger was signed as associate announcer, with Red Barber of WLW, Cincinnati, as chief. The pair worked eight games together, Barber relating the running account and Sayger contributing atmosphere, "side-lights," chats from the dressing rooms, talks from the grandstand, and so on. He carried a short-wave sending set wherever he went and was thus able to interview spectators in the boxes, players and coaches on the field and benches, and relay these interesting bit to the main wire in the radio room, and thence to the air fan via WLW.

His widow, who knew him from her grade-school days in rural Tiffin and started working for him shortly after her high school graduation in 1933, remembered those days when he illustrated books on athletics and she was the fill-in artist. Once, she said, he sent a book to be approved by a coach on his board of directors and received the reply: "Sayger, you know more than we'll ever know." He sold the books to colleges and traveled extensively. He came up with the idea of a pocket handbook of 350 to 400 schedules of college teams, taking it to a friend at Ohio Oil (now Marathon) at nearby Findlay with the idea of circulating the schedules. An advertising man was called while Sayger was still in the office and a project was born; the schedules were distributed to college alumni. Mrs. Sayger also said that he was the first to write an all-sports pictorial magazine, which was called "Sports Spotlight." He is also credited with publishing the first set of hand signals for football officials.

He took pictures on his travels, and when he sometimes had trouble getting film back on time from a nearby camera store, he bought the store in 1933. By 1940, the business included cameras and advertising specialities. He took over a printing plant and moved it downstairs. The company made photo cuts for newspapers and provided photostating. "There was no end to what he did," Mrs. Sayger said.

"I loved everything he tried," she added. "We had so much in common. He was a great person to work for. People loved him. He was so kind, and always thought of the other fellow." His time was still occupied by writing and composing music, but, as Mrs. Sayger said, "he got into lots of things. He was never idle. He took correspondence courses in everything. He was a tremendous worker"

"He loved athletics and music," said Mrs. Sayger, who was married to him only a few years before his death (he had been a widower). "He practiced by the hour when he was growing up, dividing his time between athletics and music."

In fact, he picked up his nickname of "Suz" after band leader, John Philip Sousa, because when he wasn't practicing basketball, he would march down the railroad track at Culver pretending he was playing an instrument. Someone said, "There goes a little Sousa," and the name stuck.

After her husband died in 1970 after contracting pneumonia on the way to a national football coaches convention in New York City, Mrs. Sayger continued the business.

All in all, it was quite a career for the young man from Culver who thought so much of the benefits of athletics that he started an award at Culver High School. He wanted the recipient each year to be a senior athlete who exemplified not only athletic ability but good sportsmanship and was well liked by his teammates. Moreover, the award winner was expected to do well in life after his high school athletic career was over.

But when the high schools at Culver, Monterey and Aubeennaubee Twp. consolidated into Culver Community High School, the Culver High School award went by the wayside.

Herman Sayger never got over his love for the Culver area, and when he died in 1970, his wish was granted:

Herman Sayger never got over his love for the Culver area, and when he died in 1970, his wish was granted:

His ashes were spread over Lake Maxinkuckee.